Why a focus on Lancaster County’s youngest kids could break cycle of poverty

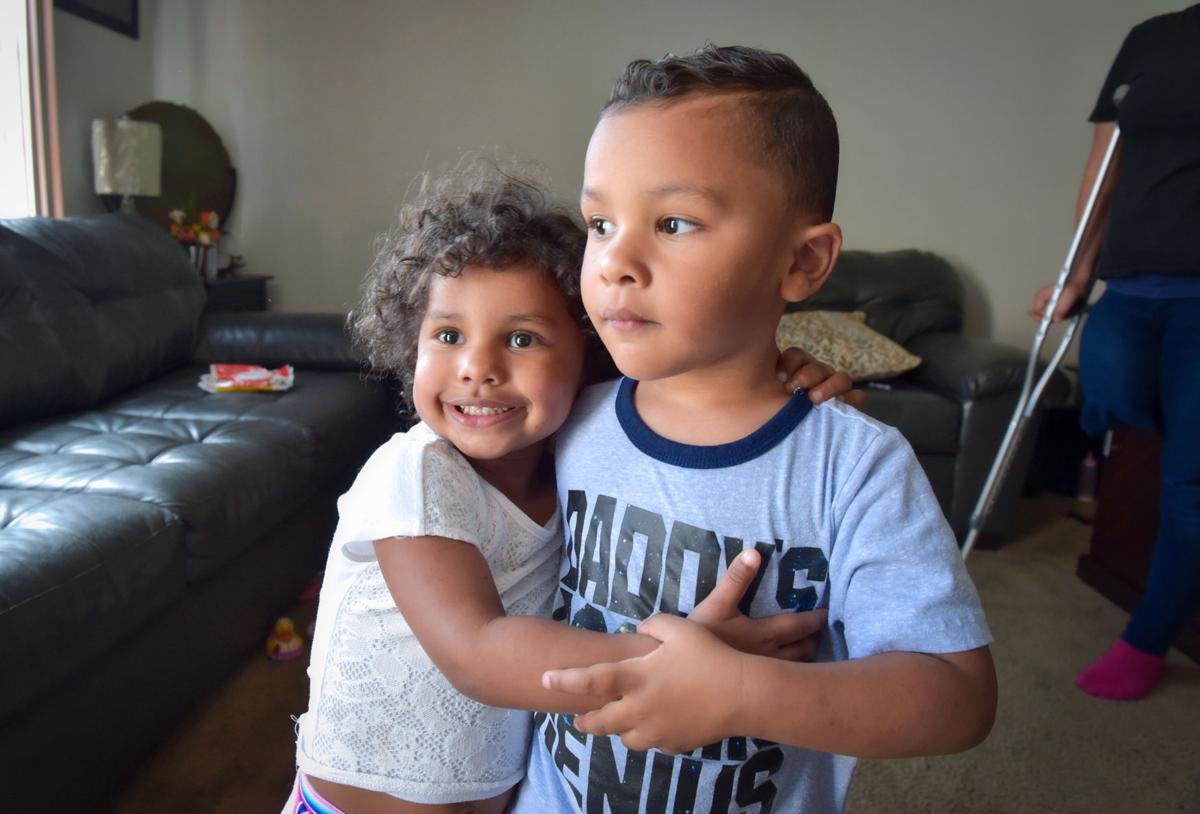

The kids leaned against Lapp as she read to them. They laughed when she barked like a dog in the story. And they vied for attention while busy with a lesson involving Popsicle sticks, cotton balls and glue sticks.

When Lapp got up to leave after 45 minutes, Immanuel didn’t want her to go. Grinning, he blocked the door, arms spread.

Lapp is a government-funded family development specialist serving 16 families with young children, and her work exemplifies the latest thinking on how to strengthen low-income families, promote school readiness and disrupt intergenerational poverty.

Head Start and other high-quality, preschool programs play a vital role in leveling the playing field for at-risk 3- and 4-year-olds. But some experts say more benefit may be gained by reaching even younger children and their parents. Because children in poverty fall behind more affluent peers at an early age, even pre-kindergarten can be too late to help them catch up.

These findings have given rise to an initiative known as prenatal-to-third-grade, or P-3 for short.

It seizes on research about the young brain’s rapid development and how nurturing or, conversely, being deprived sets the stage for success or problems down the road.

“The achievement gap exists in kindergarten,” said Andrea Heberlein, a United Way staffer and P-3 advocate who oversees an education task force for the Coalition to Combat Poverty. “That to me is the headline.”

This story is about the effort to create P-3 systems in Lancaster County and how a more intentional focus on early learning could benefit children like Immanuel and Gigi.

Their mother, Anna Rodriguez, 38, of East Lampeter Township, is single, unemployed and also raising two teen daughters. Wanting help for her preschoolers, she sought out the home-visiting program Parents As Teachers, a key link in the P-3 continuum.

What Rodriguez didn’t expect was how supportive Lapp would become as she raised her children and studied to earn her GED diploma. Lapp was a sounding board, a shoulder to cry on and the mentor Rodriguez never had.

GED class

Seamless network

For seven years as principal at high-poverty Fulton Elementary School, Jill Koser stayed alert for ways to boost her students’ achievement.

Now she realizes she missed an opportunity.

It hadn’t dawned on her to visit day care centers in the neighborhood even though they were teaching her school’s future students.

How much better prepared they would be for kindergarten if she had partnered with the centers. Day care teachers could have understood the school’s needs. Kindergarten teachers could have met their future students and their families.

Now Koser is the education and child development leader at Community Action Partnership, where she has become the county’s biggest champion of prenatal-to-third-grade.

Research backs up the value of working with vulnerable families as early as possible — even before the mother gives birth — and of sustaining support until the youngest child finishes third grade.

P-3 advocates also emphasize seamless transitions as children age into new programming. A long-standing divide exists between those who work with children ages 0 to 4 and those who work with children from kindergarten on up.

The benefits of bridging that gap are self-evident.

Early childhood educators can prepare a child for the exact expectations the school has for incoming kindergartners. And teachers and principals can get a comprehensive profile of a child’s needs before that first day of kindergarten. As logical as that sounds, too often schools start from scratch.

When Koser, the former Fulton principal, heard a speaker at a conference last summer explain the transformative power of P-3, her eyes were opened.

The United Way’s director of community impact, Andrea Heberlein, also attended, and the pair left the conference galvanized.

They secured funding to bring consultant David Jacobson of Massachusetts’ Education Development Center, the P-3 conference’s speaker, to Lancaster for three days in May to jump-start action. He met with groups of community and education leaders.

P-3 “is the leading edge of reform,” Jacobson told nearly 40 at one of the sessions. “This is the single most powerful approach that we have to improve outcomes for low-income children in the United States.”

He expressed optimism that P-3 can transcend the country’s political divide because both conservatives and liberals understand the importance of a child’s first eight years.

While Lancaster County lags some areas of the country in adopting P-3, Jacobson said, “You’re ahead of a lot.”

JEFF HAWKES |Staff Writer

Suzanne Morris, Pennsylvania’s deputy secretary for childhood development and early learning, in an interview held up Pittsburgh as a P-3 pioneer in Pennsylvania, but confirmed that Lancaster County is making strides.

“I think of Lancaster as a local leader in the early learning space,” Morris said. “They have such a deeply connected community. They really do talk to one another. That serves as an example for the state as a whole.”

United Way funds

If P-3 does take off in Lancaster County, two key players will have done their work well. They are an education task force with the poverty coalition and a new United Way-funded collaborative called P-3 Partnership Pathways.

The P-3 Partnership received $298,000 from the United Way to hire a P-3 coordinator and increase options for preschoolers in the Ephrata, Lancaster, Manheim Central and Penn Manor school districts.

Koser is a leader with both groups.

“Clearly, we have a green light,” Koser said of pushing P-3 forward. “There’s a lot of interest. People want to get it moving.”

Six of 16 Lancaster County school districts, for example, are finding ways to cooperate with early-childhood programs.

“As a superintendent I feel compelled to reach beyond my official scope of responsibilities in order to give kids their best shot,” said Robert Hollister, who is exploring P-3 as superintendent of Eastern Lancaster County School District. “If we’re going to do best for kids, we need to help parents set the stage for kindergarten.”

Koser offered a vivid example from her time at Fulton. One year a student entered kindergarten with lots of problems. The child was aggressive and nearly nonverbal. The parents had felt so overwhelmed with the child’s challenges, they rarely let the child leave the apartment.

Once the child was in school, specialists diagnosed autism-like features, and the school got extra help. The parents, who had been blaming themselves for their “bad” kid, were relieved. Five years later, the child is doing much better.

But Koser knows precious time was lost.

“We should have gotten to that kid” earlier, she said. “If we had a strong (P-3) system … we could have seen the results much more quickly. We’re five years off the growth (the child) potentially could have experienced.”

Math tutor

JEFF HAWKES | Staff Writer

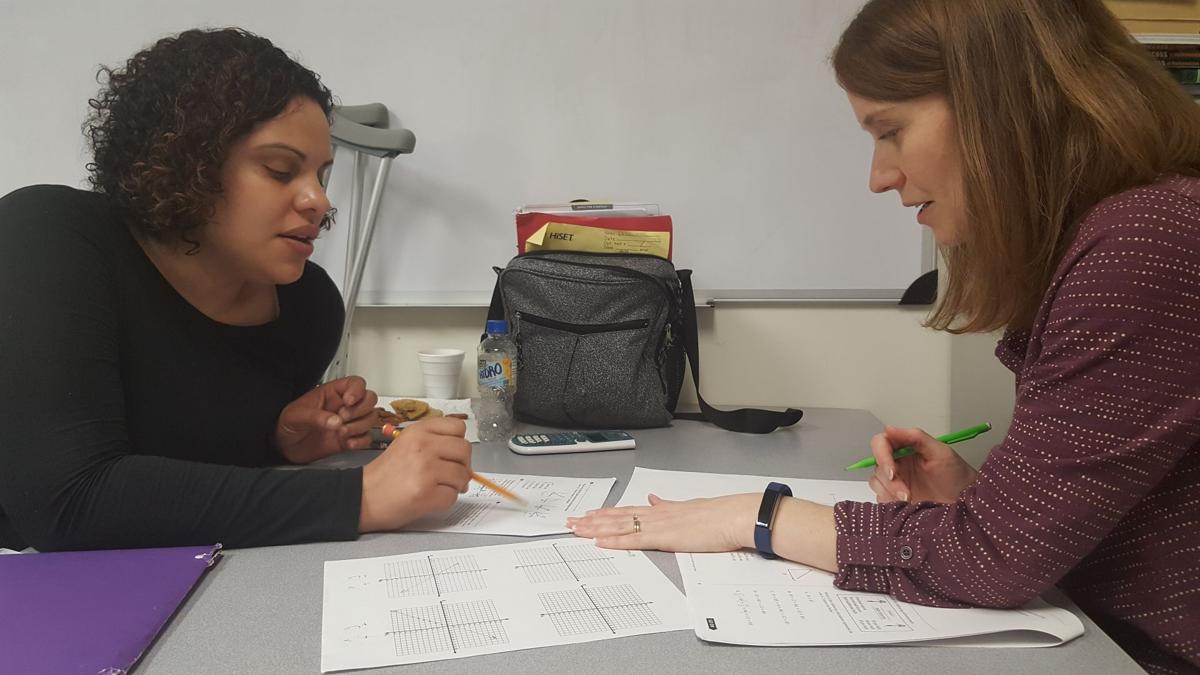

Exponents, square roots, equations. Those concepts, among others, tripped Rodriguez up in May as she twice sat for the GED math test and twice failed to clear the final obstacle in her path to earning the job market’s door-opening credential.

She took the setback hard. Lapp listened, sympathized and assured her she would bounce back.

Lapp also had a bright idea. She knew a college student who was home for the summer and asked her if she’d like to tutor Rodriguez.

Kayla Heine, 20, who is studying psychology and Mandarin at Smith College, agreed.

On a recent Tuesday evening, Heine and Rodriguez settled at a table in a tiny room at Manheim Township Public Library for the second of their weekly sessions.

Heine came well prepared. She had reviewed a GED test prep book, and in her own hand, she had created practice sheets. She patiently reviewed inverse functions, the combination of terms and the order of operations with Rodriguez.

“It does seem like they throw a lot of things at you on the test,” Heine said.

Rodriguez engaged in the work. For her sake and her children’s future, she knew she had to stay the course.

But school was out, and her kids, she told Heine, were “wanting to go here and there.”

The demands were unrelenting, and she felt spent. For solace, she had gone to church the previous evening.

Rodriguez also admitted to lingering disappointment. She had passed the reading, writing, social studies and science sections of the GED. Why was math giving her such trouble?

“It seems so hard, and it seems like so much, but I don’t want to give up,” she said. “I hate it. But I know I can do it.”

“That’s why we’re here,” Heine said.

“Practice, practice, practice,” Rodriguez said.

Nodding, Heine said, “OK, let’s go over one more.”

DAN MARSCHKA | Staff Photographer